Back Maksimiliaan I Afrikaans Maximilian I. (HRR) ALS Maximilián I d'Habsburgo AN ماكسيمليان الأول (إمبراطور روماني مقدس) Arabic ماكسيمليان الاول (امبراطور رومانى مقدس) ARZ Maximilianu I d'Habsburgu AST I Maksimilian (Müqəddəs Roma imperatoru) Azerbaijani بیرینجی ماکسیمیلیان (ایمپیراتور) AZB Максимилиан I (Изге Рим империяһы императоры) Bashkir Максіміліян I Габсбург Byelorussian

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 23,583 words. (May 2024) |

| Maximilian I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Albrecht Dürer, 1519 | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 4 February 1508 – 12 January 1519 |

| Proclamation | 4 February 1508, Trento[1] |

| Predecessor | Frederick III |

| Successor | Charles V |

| King of the Romans King of Germany | |

| Reign | 16 February 1486 – 12 January 1519 |

| Coronation | 9 April 1486 |

| Predecessor | Frederick III |

| Successor | Charles V |

| Alongside | Frederick III (1486–1493) |

| Archduke of Austria | |

| Reign | 19 August 1493 – 12 January 1519 |

| Predecessor | Frederick V |

| Successor | Charles I |

| Duke of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 19 August 1477 – 27 March 1482 |

| Predecessor | Mary |

| Successor | Philip IV |

| Alongside | Mary |

| Born | 22 March 1459 Wiener Neustadt, Inner Austria |

| Died | 12 January 1519 (aged 59) Wels, Upper Austria |

| Burial | |

| Spouses | |

| Issue more... | Illegitimate : |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Eleanor of Portugal |

| Religion | Catholic Church |

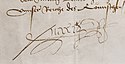

| Signature |  |

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians.[2] He proclaimed himself elected emperor in 1508 (Pope Julius II later recognized this) at Trent,[3][4][5] thus breaking the long tradition of requiring a papal coronation for the adoption of the Imperial title. Maximilian was the only surviving son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, and Eleanor of Portugal. Since his coronation as King of the Romans in 1486, he ran a double government, or Doppelregierung (with a separate court), with his father until Frederick's death in 1493.[6][7]

Maximilian expanded the influence of the House of Habsburg through war and his marriage in 1477 to Mary of Burgundy, the ruler of the Burgundian State, heiress of Charles the Bold, though he also lost his family's original lands in today's Switzerland to the Swiss Confederacy. Through the marriage of his son Philip the Handsome to eventual queen Joanna of Castile in 1496, Maximilian helped to establish the Habsburg dynasty in Spain, which allowed his grandson Charles to hold the thrones of both Castile and Aragon.[8] The historian Thomas A. Brady Jr. describes him as "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned" and also, the "ablest royal warlord of his generation".[9]

Nicknamed "Coeur d'acier" ("Heart of steel") by Olivier de la Marche and later historians (either as praise for his courage and soldierly qualities or reproach for his ruthlessness as a warlike ruler),[10][11] Maximilian has entered the public consciousness as "the last knight" (der letzte Ritter), especially since the eponymous poem by Anastasius Grün was published (although the nickname likely existed even in Maximilian's lifetime).[12] Scholarly debates still discuss whether he was truly the last knight (either as an idealized medieval ruler leading people on horseback, or a Don Quixote-type dreamer and misadventurer), or the first Renaissance prince—an amoral Machiavellian politician who carried his family "to the European pinnacle of dynastic power" largely on the back of loans.[13][14] Historians of the second half of the nineteenth century like Leopold von Ranke tended to criticize Maximilian for putting the interest of his dynasty above that of Germany, hampering the nation's unification process. Ever since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971–1986) became the standard work, a much more positive image of the emperor has emerged. He is seen as an essentially modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial price weighed hard on the Austrians and his military expansion caused the deaths and sufferings of tens of thousands of people.[11][15][16]

Through an "unprecedented" image-building program, with the help of many notable scholars and artists, in his lifetime, the emperor—"the promoter, coordinator, and prime mover, an artistic impresario and entrepreneur with seemingly limitless energy and enthusiasm and an unfailing eye for detail"—had built for himself "a virtual royal self" of a quality that historians call "unmatched" or "hitherto unimagined".[17][18][19][20][21] To this image, new layers have been added by the works of later artists in the centuries following his death, both as continuation of deliberately crafted images developed by his program as well as development of spontaneous sources and exploration of actual historical events, creating what Elaine Tennant dubs the "Maximilian industry".[20][22]

- ^ Cuyler 1972, p. 490.

- ^ Weaver 2020, p. 68.

- ^ Emmerson 2013, p. 462.

- ^ Stollberg-Rilinger 2020, p. 13.

- ^ Whaley 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Wolf, Susanne (2005). Die Doppelregierung Kaiser Friedrichs III. und König Maximilians (1486–1493) (PDF) (in German). Köln. pp. 561, 570. ISBN 978-3-412-22405-9. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Heinig, Paul-Joachim (15 June 2010). "Rezension von: Reinhard Seyboth (Bearb.): Deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Maximilian I. Vierter Band: Reichsversammlungen 1491–1493, München: Oldenbourg 2008" [Review of: Reinhard Seyboth (Ed.): German Reichstag files under Maximilian I. Fourth volume: Reich assemblies 1491–1493, Munich: Oldenbourg 2008]. Sehepunkte (in German). 10 (6). Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Holland, Arthur William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 922–923 [922].

...and about the same time arranged a marriage between his son Philip and Joanna, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, king and queen of Castile and Aragon.

- ^ Brady 2009, pp. 110, 128.

- ^ Terjanian 2019, p. 37.

- ^ a b Hollegger 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Fichtner 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Trevor-Roper 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Vann, James Allen (Spring 1984). "Review: [Untitled]. Reviewed work: Maximilian I, 1459–1519: An Analytical Biography. by Gerhard Benecke". Renaissance Quarterly. 37 (1): 69–71. doi:10.2307/2862003. JSTOR 2862003. S2CID 163937003.

- ^ Whaley 2012, pp. 72–111.

- ^ Hollegger, Manfred (25 March 2019). "Maximillian Believed in Progress". oeaw.ac.at. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Munck, Bert De; Romano, Antonella (2019). Knowledge and the Early Modern City: A History of Entanglements. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-429-80843-2. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Hayton 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 128.

- ^ a b Terjanian 2019, p. 62.

- ^ Whaley 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Tennant, Elaine C. (27 May 2015). "Productive Reception: Theuerdank in the Sixteenth Century". Maximilians Ruhmeswerk. pp. 295, 341. doi:10.1515/9783110351026-013. ISBN 978-3-11-034403-5. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search